What Is Worth Preserving? On Art, Meaning, and the Refusal to Become a Machine

In an age of AI, CNC machines, and endless replication, a stone carver reflects on what truly gives art its worth. A meditation on message, meaning, and creating from the heart.

What is worth? What truly matters?

For the artist—whose life’s work is to interpret the world and reveal it back to others as faithfully as possible—these questions are unavoidable. We are lenses, shaped by perception, memory, belief, and experience. What we see, and how we choose to show it, matters.

Yet most people live at the surface.

We absorb culture, news cycles, feeds, and opinions as they’re handed to us—rarely slowing down, rarely going inward. Depth is traded for immediacy. Noise replaces meaning. And somewhere beneath it all, the question of what is actually worth saying gets buried.

Values matter.

They are the reason we take the stairs instead of the elevator—straining upward when no one is watching. They are the quiet force behind endurance, behind choosing difficulty for the sake of growth. Joseph Campbell called it the Hero’s Journey. But what is that journey for an artist?

I hope it goes beyond monetization.

Not producing merely to meet demand.

Not making objects to satisfy an algorithm or a market trend.

But creating for the message—not just the medium.

I was once asked a question that haunts many traditional craftspeople:

“Why carve stone by hand when a CNC machine could do it faster?”

I gave the expected answer—about time, intention, uniqueness, and how collectors value the human touch. All true. But the deeper answer came later.

We are not machines.

We are not CNC routers.

We are not AI models assembling images from databases of copies of copies.

We are the mind, the temperament, the patience, the struggle, and the heart behind the message.

A machine can replicate form.

It cannot excavate meaning.

AI generates images by averaging what already exists. CNC machines execute instructions flawlessly—but blindly. They do not wrestle with doubt. They do not pause in reverence. They do not fail, recover, or change course because something felt wrong.

What we do—what artists do—is hollow meaning out of the depths of lived experience and place it on display. That message can be copied, replicated, automated—but only after it has first been found. And that finding is human.

Yes, our labor is slow.

Yes, it is tedious.

Yes, it often feels like Renaissance work carried out on a 21st-century timeline.

Shortcuts are tempting—and sometimes necessary. But the goal has never been speed. The goal is clarity. Honesty. Saying something that matters.

Stone carving may look old. It may not appear revolutionary. But it is not the medium that matters—it is what is said through it. And often, even the artist doesn’t fully understand the message at first.

It must be done with the heart.

We carve our own stream, even knowing it will eventually join a river shaped by countless others. But the water is clean where it emerges. It is yours. No one can tell you where it leads—but it must be followed.

Some call this “following your bliss.”

Others call it vocation.

It is that thing you would do even if it paid nothing. Even if it cost you comfort. Even if it demanded sacrifice. Not for ego—but for service. For offering something true to others. And for aligning with something larger than yourself.

Remember this:

You matter.

Your message matters.

And the world does not need one more copy of a copy.

Do not let what you carry be lost.

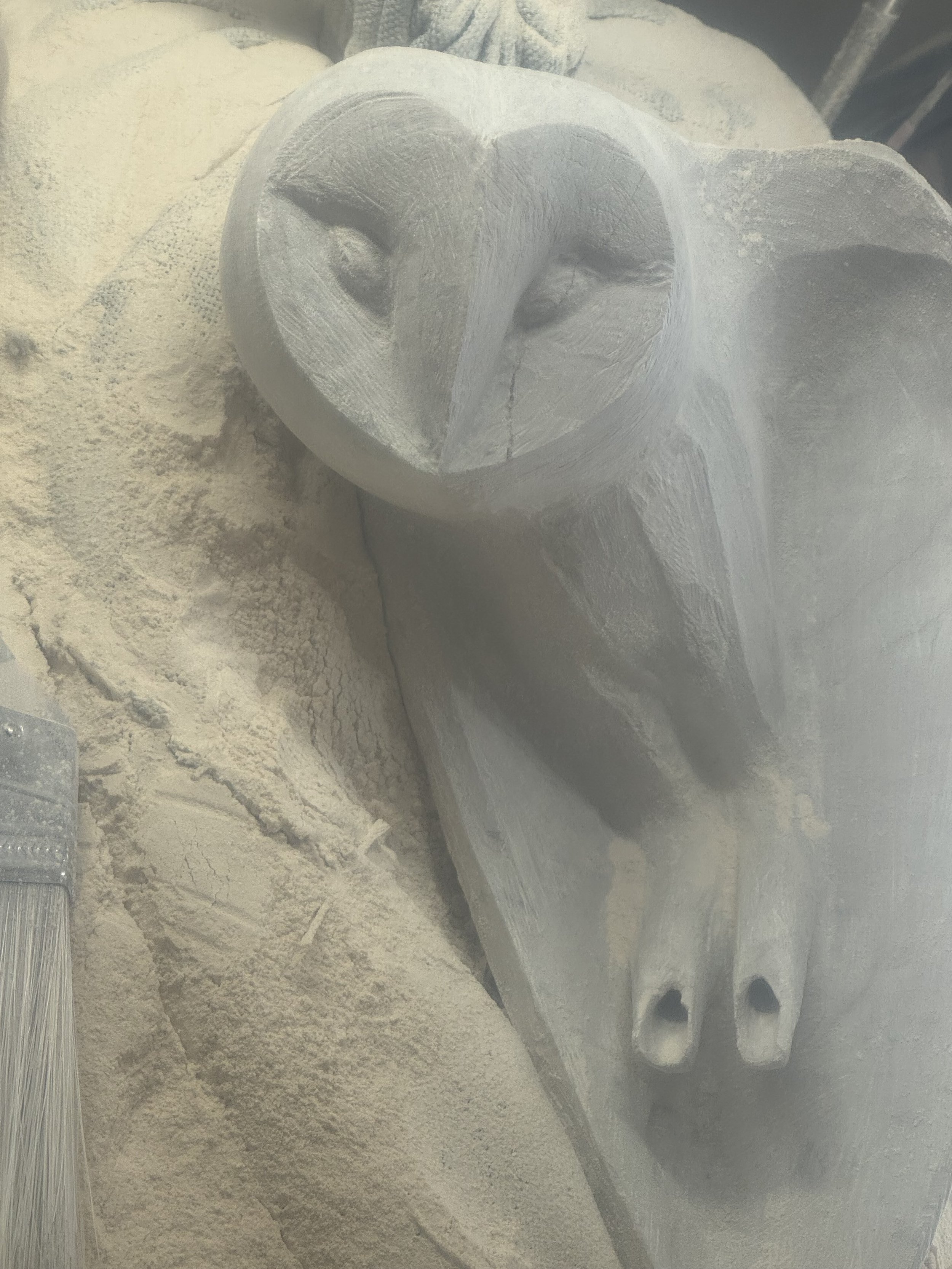

Anima, the Barn Owl, and the Threshold Beneath the Wing

From Mesopotamian reliefs to esoteric symbolism, the barn owl has long been tied to hidden knowledge, liminal spaces, and the silent weight of ancient memory.

I’ve had a bit of time recently to return to another barn owl project, and as often happens when I work with this form, it’s pulled me back into deeper reflection. Not just about anatomy or gesture—but about why this animal continues to surface in human imagination, across cultures and eras.

The barn owl feels less like a subject and more like a metaphor that predates us.

Across history, the owl has occupied a complicated and often contradictory role. In parts of Africa, owls have long been associated with witchcraft and shapeshifting, seen as emissaries between worlds or forms assumed by practitioners who move unseen. In other traditions, particularly within early Western esoteric and fraternal symbolism, the owl becomes a figure of hidden knowledge, night wisdom, and watchfulness—sometimes even linked, symbolically, to darker or more ambivalent forces.

There are interpretations that connect the owl to Molech imagery within early fraternity symbolism—often pointed out in discussions of the American dollar bill, where the owl is said to hide in the folds and corners. Whether literal or symbolic, these readings speak less to historical certainty and more to the owl’s enduring association with secret knowledge, thresholds, and power held in silence.

What’s striking is how far back this goes.

The earliest known appearances of owl imagery appear in Mesopotamia, and possibly even earlier. The most well-known example is the so-called Burney Relief (often linked to Lilith), where owls flank a winged female figure—an image saturated with themes of night, sexuality, sovereignty, and the liminal. In these early contexts, the owl is not softened or romanticized. It is potent, unsettling, and deeply tied to the unseen forces of the psyche and the world.

This is where Anima continues to live for me.

In Jungian psychology, the anima represents the inner soul-image—the intuitive, unconscious, feeling aspect of the psyche. It is not polite. It does not speak loudly. It appears in symbols, dreams, animals. The barn owl, nocturnal and soundless in flight, feels like a perfect carrier of this energy: perceptive without display, powerful without aggression.

As I worked on this piece, my attention kept returning to a small but essential structure: the tarsus.

In the anatomy of the barn owl, the tarsus is the quiet pillar of balance—the slender segment that carries weight, absorbs stillness, and allows the body to remain suspended between earth and air. It is a place of grounding rather than motion, often unseen, yet essential.

Though it shares no linguistic origin, the word tarsus echoes the ancient city of Tarsus, a historical crossroads where philosophies, religions, and inner traditions converged. The parallel is symbolic rather than etymological—but meaningful nonetheless.

Here, the tarsus becomes a metaphor:

a threshold between movement and rest,

between the visible and the unseen,

between instinct and awareness.

Like the owl itself, this form occupies the liminal—rooted firmly in the physical world while oriented toward the silent, the nocturnal, and the intuitive. The strength lies not in force, but in steadiness; not in flight, but in what makes flight possible.

In returning to the barn owl, I don’t feel like I’m repeating myself. I feel like I’m circling something ancient—something that keeps revealing itself slowly, layer by layer. Perhaps that is the nature of Anima itself: not something to be solved, but something to be approached with patience, weight, and listening.

Learning to See for Yourself

David Hockney once said that being an artist is a privilege — an act of interpreting life itself. In an age of viral spectacle and hollow fame, learning to see and create for yourself may be the most honest rebellion an artist can make.

David Hockney once said in an interview:

“I think a lot of people would like to be artists. What you’re doing is interpreting life. You’re interpreting your experience, and it’s a privilege in a sense to be able to do that.”

I believe this is profoundly true. Awakening to the ability to see the world — and then recreate that reality through your own hands — is a gift worth cherishing. There is so much in this life that needs to be learned, taught, and passed along, and each of us does this in a way as unique as our own personality. The way you see is not a flaw. It is perfect in its own way.

Anyone who has spent time in an art class knows this instinctively. Place a group of people in front of the same reference image, give them the same medium, and ask them to copy what they see. The results will always be wonderfully different. Yes, skill levels vary — but that’s not the point. What matters is that each person is learning how they observe, interpret, and project what they see. Every attempt deepens perception. Every repetition refines understanding. Growth happens not through imitation alone, but through honest self-reflection layered into the process.

What troubles me about much of contemporary art culture — especially in art schools and viral platforms — is the growing admiration for what I’d call effortless spectacle. Work that requires little time, little discipline, and little practical investment, yet thrives on flashy presentation and algorithmic manipulation. Attention becomes currency. Funding follows clicks. Eventually, the work itself becomes secondary to the performance around it.

At some point, it no longer matters whether the artist has depth or skill — only that they appear important. Prices inflate like speculative assets, untethered from meaning, until repetition alone cements their place in textbooks. The system validates itself.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: sometimes we need to call it out.

If a piece of art doesn’t resonate after an honest, patient attempt to understand it — if it fails to speak in any meaningful way — it’s possible you’re not missing something. It’s possible you’ve been duped. When art requires a tour guide, a manifesto, or relentless self-promotion just to justify its existence, it may be the surrounding noise doing the heavy lifting — not the work itself.

Your attention is valuable. You don’t owe it to the algorithm. You don’t owe it to trends. You don’t owe it to charisma, bravado, or carefully curated personas. Too often, the art becomes inseparable from the figure behind it, and the object itself loses its voice.

The antidote to this isn’t cynicism — it’s practice.

Learning to make art for yourself, in your own way, is one of the most awakening acts you can undertake. It teaches you how to see clearly. It sharpens discernment. It reconnects you to what feels honest and alive. Creating isn’t about chasing recognition — it’s about becoming the thing you once wished existed.

Learn to see for yourself.

Create for yourself.

That’s where meaning still lives.

What Pressure Reveals

Sometimes pressure strips everything away but what matters. A reflection on survival, responsibility, and how intensity shapes the deepest work.

Two years ago—though it feels both distant and immediate—I was home with a one-month-old daughter when a gallery asked if I could prepare three finished sculptures by May.

For many artists, that might sound manageable. For me, it was daunting.

I am not a production artist. I don’t replicate forms endlessly or work half-consciously while something hums in the background. Each piece takes time—sometimes painful time. Ideas arrive slowly, shaped by contemplation, doubt, and the need for each work to be distinct from the last. Nothing happens overnight, and when it does happen quickly, it usually hurts.

Still, I agreed.

At the time, I was working ten-hour shifts, often driving coworkers home afterward. Some nights I’d run a short loop just to clear my head, then head straight into the basement, pulling on overalls and carving until exhaustion made it unsafe to continue. This was during a two-week rotation, which meant working Saturdays as well. Sleep became a deficit. If eight hours was the goal, I was living on four to six—sometimes less.

And yet, the work I produced during that period remains among my strongest.

The Role of Pressure

Looking back, I understand why. The request from a reputable gallery, combined with the responsibility of providing for a newborn, created a pressure I couldn’t escape. Survival became motivation. The desire to be better than yesterday wasn’t philosophical—it was necessary.

That kind of pressure strips away excess. It forces clarity. It reveals what matters.

I was reminded of this recently in an entirely different context.

A Night in the Storm

After a family gathering nearly an hour and a half away, I began driving home through worsening snow squalls. Visibility dropped to nothing, then cleared just long enough to reveal another drift ahead. The road became a tunnel of white noise and instinct.

I had good tires. A solid vehicle. Music loud enough to keep me alert. There was a strange focus that set in—the kind that appears when there’s only one job: get through.

Near home, I realized I’d made a selfish mistake. My brother was still stranded nearly an hour back, stuck in the middle of nowhere as conditions worsened. Without much hesitation, I turned around.

What followed was hours of frozen wind, soaked clothing, cars abandoned in ditches, pulling strangers free, getting stuck myself, then helping coordinate a long, roundabout rescue. At one point, I rolled into a gas station with the gauge reading negative distance—somehow still moving, rationed by the hybrid system just long enough to survive the last stretch.

I was wired. Focused. All or nothing.

My sister-in-law later told me she didn’t recognize my voice when I spoke to her. That survival self had taken over.

Why This Matters to Art

As viewers, it’s easy to miss what goes into a finished work. The sweat. The exhaustion. The moments where failure feels imminent.

Van Gogh is an obvious example—not because of his suffering alone, but because his work holds both torment and grace at once. We feel it. His paintings carry the tension between despair and reverence for life, fused into something enduring.

I believe that kind of intensity—whether born of necessity, responsibility, or sheer will—brings us closer to our core selves. When an artist works from that place, something transfers through the medium. Not consciously. Not deliberately. But unmistakably.

What Endures

Sometimes, it’s the need to overcome—regardless of circumstance—that deepens the value of the work. Not because suffering is noble, but because pressure reveals truth. It strips away pretension and leaves only what’s essential.

When that drive finds its way into the work, it gives the piece a pulse. A weight. A presence.

And perhaps that’s what we respond to most—not perfection, but the quiet evidence that someone pushed through something real to bring it into being.

What Is Worth Framing?

In an age of spectacle and hype, what is truly worth framing? A reflection on modern art, attention, and learning to see again.

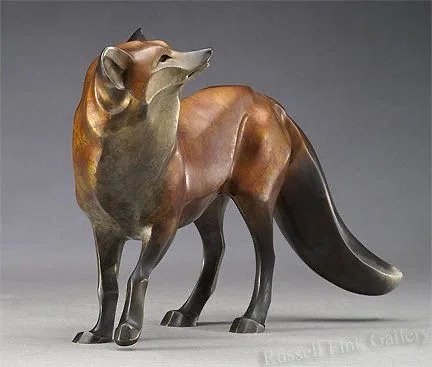

Recently, I found myself lightly amused—and occasionally frustrated—by the social media presence of a well-known traditional sculptor whose bronze works are widely respected. His Instagram feed frequently mocks contemporary artists who chase novelty without effort, skill, or depth—artists whose work leans more on cultivated cult followings than on craft itself.

The videos he shares are familiar: crowds gathered around vague performances, stick-figure gestures, objects waiting to fall, or a single moment of slapstick absurdity stretched thin. When it ends, applause follows—hesitant at first, then enthusiastic—less out of understanding than relief that something happened. Moments later, the performance is praised as revolutionary, though no real movement, insight, or transformation occurred.

I don’t entirely disagree with the critique. Every generation produces the occasional work that genuinely reshapes the landscape of art—but those moments are rare. Needles in haystacks. What we’re often left with instead are fleeting spectacles, destined to fade once the novelty wears off.

It reminds me of the alt-coin era in crypto: thousands of coins rising and falling without purpose or intrinsic value, built on hype rather than substance. Years from now, most will be forgotten entirely, their names rewritten out of the cultural memory along with the lessons they failed to teach.

Manufactured Meaning

For a long time, I wondered why certain figures—Pollock, Warhol, Rothko—were elevated to such mythic status. Eventually, I arrived at a less romantic conclusion. Much of modern art’s canonization was driven by cultural, political, and economic forces rather than pure artistic merit. Abstract expressionism, for example, was actively promoted as a psychological counterweight to socialism and communism—an image of unrestrained freedom.

Rothko, in particular, strikes me as less a painter of depth and more a master rhetorician—someone who could persuade you that a blank canvas held transcendent meaning, if only you were enlightened enough to feel it. And perhaps that persuasion was the work itself.

The uncomfortable truth is this: we are constantly framed into believing things are meaningful simply because we’re told they are. Put nearly anything on a wall, surround it with authority, and people will work hard to convince themselves it matters.

So What Is Worth Framing?

This is where my frustration gives way to a more important question.

What is actually worth holding our attention?

A work of art, at its best, carries light within structure. It asks something of us—not applause, not allegiance—but presence. It deserves a moment of our lives because it gives something back: insight, beauty, humility, wonder, or truth.

Too much of our attention today is siphoned away by spectacle. By artists who trade depth for fame, and sincerity for virality. Your attention is worth more than that.

Learning to See Again

The next time you walk through a gallery—or scroll past one online—pause. Don’t give yourself to the loudest work, the cleverest provocation, or the piece engineered to steal attention like a catchy commercial jingle.

Listen instead for what carries wisdom. For what holds life quietly within it.

If there is real light in a work, it won’t demand your praise. It will illuminate something inside you—and allow you to become more fully yourself, not a reflection of someone else’s performance.

Between Stone and Becoming

An honest reflection on recent sculptures, future projects, and the inner work of choosing growth, freedom, and intention—both in art and in life.

Much of what I write tends to circle around meaning—art as symbol, as prayer, as something larger than ourselves. But it feels right to pause and offer a more grounded update: what has been happening in the habits, worries, hopes, and small victories of this very feeble human behind the work.

Last month, I found the time and focus to finish six pieces: three inuksuks and three birds. A modest achievement by most measures, yet each piece carried my heart in its own way. Letting them go is never easy—especially when pricing them means balancing emotion with the practical need to grow. Tools must be bought. Stone must be sourced. Future projects must be funded.

And let me tell you—there is always something coming. I tend to keep a couple thousand dollars’ worth of plans quietly waiting in the wings. It sounds ambitious, perhaps even excessive, but my plans have always been taller than I am. Growth asks for that. A small heart stretches by reaching just a little further each time, taking slightly longer journeys, testing the edges of what feels possible.

Looking Ahead

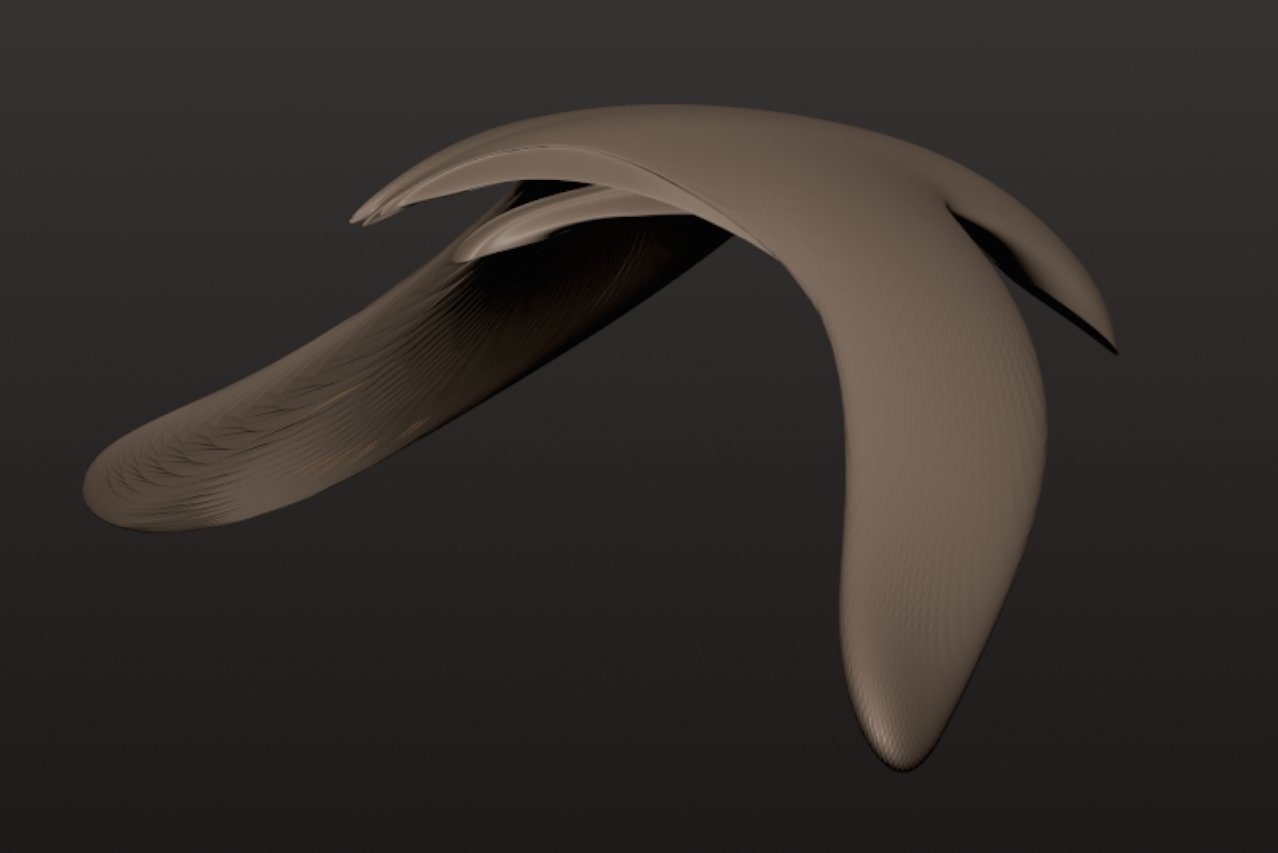

One upcoming project is a Great Egret—an undertaking that excites me deeply and intimidates me just as much. Anyone familiar with the bird can imagine the challenge: long, delicate proportions, elegance in motion, all translated into alabaster. The technical demands are immense. I’ve already spent hours working through multiple 3D renders, studying anatomy and balance, refining the form before stone ever meets tool.

And honestly—that excitement is what matters most. When curiosity is alive, the work is already halfway done.

Letting Work Find Its Place

Another moment that stayed with me was delivering the recent birds and inuksuks to the gallery as promised. While there, the gallery owner shared a discreet note about the collector who had acquired my last owl—anonymous, but described as a particularly discerning and respected collector.

Art means something personal to every collector, but knowing that a thoughtful, experienced eye chose one of my works does stir a quiet pride. More than that, I felt relief. Relief knowing the piece now rests somewhere it will be cared for, highlighted, and allowed to speak for itself. That owl stayed close to me for a long time. Rarely do I finish a piece and feel no urge to change it weeks later—but that one held.

On Change and Choice

All of this led me to a reflection I’ve been carrying this past week: we are always changing, whether we notice it or not. Our minds are freer than we often believe—if only we learn how to unlock the doors we’ve built ourselves.

Fear has a way of disguising itself as practicality. It nudges us toward self-sabotage, toward small compromises that slowly dim our potential. But change is unlocked through choice. We are, each of us, the captain of our own soul—hands on the rudder, steering either toward open waters or onto the rocks of familiar, lost islands.

What we choose to do with our time today—whatever portion of it we still hold—reshapes our tomorrow. Freedom begins there. Not in grand gestures, but in choosing not to live as a slave to circumstance.

We all believe this, deep down. We know it from the inside out.

As Maximus said in Gladiator:

“What we do in life echoes in eternity.”

When the Mind Steps Aside: Discovering the Hidden Hand in Art

I believe I’ve stumbled upon something remarkable—perhaps even groundbreaking—about how we live and create with intention. It’s an insight into what happens when we trick the left brain—that logical, critical part of ourselves—into stepping aside long enough for something greater to emerge.

My high school art teacher used to say, “Let the right brain take over.” He’d crank up the music, stop teaching technical details, and just let us create. The idea was simple: music and rhythm help us shift from the analytical left hemisphere to the intuitive right. In that space, we loosen up. We begin to feel more than think.

Neurologically speaking, when the left brain quiets down, we can enter a blissful, flow-like state. But if it shuts off completely, we lose access to logic, speech, or even basic coordination. So the magic seems to live in that in-between—where intellect hums quietly in the background while intuition takes the lead.

The Experiment with My Daughter

A few days ago, I was looking at Pinterest images of polar bears before sitting down to draw with my daughter. She loves to scribble freely, without rules or expectations. Sometimes she’ll glance at her drawing and casually say, “cat,” or “bird,” and sometimes I may grasp something alike out of it.

Inspired, I decided to draw the way she does—fast, loose, without trying. About 25 seconds in, while my hand moved almost unconsciously, a polar bear’s face began to appear from the chaos of scribbles. Upside down, no less. And astonishingly, it was better—more alive—than what I could have drawn had I tried.

A few days later, I tested it again—drawing upside down this time while she watched from across the table. Again, the result was more natural, more expressive, more true.

The Great Egret Revelation

Recently, I was refining a 3D model of a Great Egret—a tall, elegant heron-like bird. I spent hours fine-tuning the proportions and details, guided by countless reference photos. Then, I put the file aside and started working on something abstract, purely for play.

And then it happened again. Out of the freeform shapes, without planning or intent, emerged the unmistakable form of a Great Egret. The likeness was uncanny—and somehow more beautiful than my deliberate, technical render.

That’s when I realized: my intellectual mind had laid the groundwork. It had studied, measured, analyzed. But it was only when I let go—when I stopped trying—that something extraordinary appeared.

The Art of Doing Without Doing

In Zen, this is known as Wu Wei (or Wei Wu Wei): doing without doing. It’s the state of effortless action, where mastery and surrender become one. The Zen archer doesn’t aim with his mind—he allows the arrow to find its target through presence.

There’s a story of a master archer who, when challenged by a student, drew his bow in complete darkness and split the back of a previous arrow. The shot was not a display of skill, but of connection—between spirit, mind, and motion.

Becoming the Instrument

In the same way, when artists let go of the ego—the “little self” that needs to control and perfect—we make space for something larger to flow through us.

Remote viewers describe a similar process: using intuition to perceive distant targets with uncanny accuracy, bypassing logic entirely. Could it be that this same something—this consciousness beyond the intellect—moves through us when we create?

Maybe true art begins where the self ends.

When we lend ourselves to something greater than our technical mind, we receive what can only be described as extraordinary. The key is learning how to let the extraordinary happen—by getting out of our own way.

Looking Up: Lessons from an Owl and the Art of Letting Go

A reflection on carving, faith, and fatherhood—how one artist found spiritual meaning in a barn owl sculpture that reminded him of his daughter and the importance of looking up.

There are times I’ve fallen in love with a sculpture as I’ve been working on it. Perhaps I’m not the only one who’s felt this way—but for me, it’s increasingly rare. The constant inner critic is always present, whispering in the background, even as the artist within searches for appreciation and gratitude in the process. At some point, those two voices—the critic and the creator—merge. And in that merging, something magical happens: flow. The careful turns careless, the mind quiets, and the stone begins to speak.

The last piece I produced began with an extraordinary reference—a young barn owl, wings slightly spread, head raised toward the sky as if watching the heavens. The posture reminded me of my daughter. That innocent, upward gaze of wonder. How often do we forget to look up as we grow older? As we stand taller, we begin to see others as peers—or worse, as competition—each of us fighting never to look up again.

But maybe looking up is exactly what we need to do more often.

Our mission, whether as artists or simply as people, is to remain teachable—to learn from something higher, to serve others as if we were entertaining the children of God. To be both young and old at once requires humility and adaptability. It calls on us to forgive, to turn the cheek, and to love even our adversaries.

When I carve an owl, I often sense that same paradox: a creature both feared and revered. Its silent watchfulness commands respect, but in its eyes I see gentleness, understanding, and beauty. In this particular owl, I saw my daughter’s spirit—bright, alert, full of promise.

So when it came time to bring the sculpture to the gallery in Niagara-on-the-Lake, it wasn’t easy. Letting go never is. Yet, I know there will be more. I will see my daughter in many future works and strive to make each piece more beautiful than the last—for love’s sake, for the art, and for whoever the piece connects with. Because in the end, we’re all connected in ways we can’t yet imagine.

When We’re Not Looking: The Quiet Birth of Beauty

Sometimes the most beautiful things in life appear when we stop trying to force them. Whether in art or life, the best creations happen when we’re not looking.

As an artist, I’ve learned the hard lesson of resting recently. If you’ve read some of my previous posts, you might sense that life has been teaching me this one the hard way. My work as a sculptor can be tedious, physically demanding, and emotionally exhausting — not only because of the stone itself but because of the expectations I build in my own mind.

I used to believe these expectations were coming from clients — that they needed something perfect, flawless, and breathtaking. But I’ve come to realize that it’s us, the artists, who forge these expectations. The truth is, clients don’t always know what to expect. It’s our job to surprise them — to create something that surpasses their imagination and reshapes their sense of what’s possible.

I should repeat that: the client has to be surprised by seeing and experiencing something that surpasses their beliefs.

That’s the real beauty of visual art. It makes people believe in something new — something they didn’t know they needed until they saw it. But ironically, the most beautiful parts of creation often happen when we’re not trying to make them happen.

I’ve noticed this again and again. Sometimes the painter’s palette is more captivating than the finished painting. The unintentional blends, the stray brush marks, the stains — all hold a kind of raw beauty that feels truer than the final piece.

I even see it in my daughter. She’ll grab a handful of markers, scatter them across the page in a flurry of colour, and something magical emerges — an unexpected harmony, a rhythm that wasn’t planned but was felt.

For the professional artist, the same thing happens. You might spend days perfecting one sculpture, but the most moving moment might be the way the dust catches the light — something you never planned or noticed until you stepped away.

It reminds me of the famous double-slit experiment in quantum physics: when no one is looking, particles act like waves — infinite, fluid, and full of possibility. Maybe creation is the same. When we stop forcing it, the beauty flows.

— “Beautiful things don’t ask to be seen.” — Sean Penn in ‘The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

Maybe that’s the quiet truth behind all art — that the best things happen when we’re not looking. When we rest, when we release control, when we make space for the impossible to happen.

So if you’re an artist (or anyone chasing something meaningful), take this to heart:

Rest. Don’t rush beauty.

Let it happen in its own time.

Art as Prayer: The Spiritual Dimension of Creation

Is art a form of prayer? From Van Gogh’s vision of art as vocation to Jesus’ call to worship “in spirit and in truth,” here’s why creativity feels divine.

Lately, I’ve been reflecting on something deeply spiritual about art. Not that art itself is a religion, but it often feels like a bridge—connecting us to the divine presence that flows through all living things.

Vincent van Gogh, perhaps more than any other artist, embodied this idea. He once called his work a “vocation,” a kind of faith. For him, painting wasn’t just craft—it was communion. He saw the divine woven into the fabric of everyday life: the stars, the fields, the people around him. When he painted The Starry Night, it wasn’t just a landscape—it was eternity itself, a vision of his soul continuing beyond death, carried into the heavens.

“I want to touch people with my art. I want them to say: he feels deeply, he feels tenderly.” — Van Gogh

Interestingly, Van Gogh once trained to be a minister but eventually left behind the formal church. Yet his art revealed something profound—that vocation need not always come through official authority. It can be lived out through the work of our hands, through creativity, through the pursuit of truth.

Art, in many ways, is a prayer. Every sculpture, every painting, every piece is a petition—an offering of meaning from the artist to the world. Sometimes its message resonates, sometimes it’s misunderstood. But if you sit quietly with art—not just glance, but really look—something beyond the surface begins to speak. Reflection opens the door to a deeper reality.

When I create, I feel this movement. The process requires me to quiet my mind, to step beyond the old self, and commit to shaping something that feels larger than me. The hours blur together. Time disappears. What remains is not just the technical outcome of my hands, but a work that feels transcendent, as if it always existed, waiting to be revealed.

It reminds me of Jesus’ words in John 4, when he told the Samaritan woman at the well that true worship isn’t confined to a place, but happens “in spirit and in truth.” That same spirit is what I believe we invoke through art: the act of perceiving and creating with honesty, reverence, and openness to the divine.

Art, at its best, is worship. Not worship of the self, or even of the object created—but of the eternal presence that flows through all things. In that way, every true act of creation is also an act of prayer.

Chasing Ghosts: The Struggle and Truth of an Artist’s Life

An honest reflection on the struggle between passion and profit, perfection and truth. Why chasing ghosts of perfection can burden us—and how staying true to our craft carries deeper meaning.

A little honesty here.

As an artist, I often wrestle with the gap between the effort I pour into a sculpture and the income it brings back. The balance is rarely even. For every hour invested in a piece, there’s the weight of tools, materials, and years of skill behind it—all against a reality where profit margins sometimes point to loss rather than gain.

If you’re not an artist, perhaps it’s easier to picture another trade. Imagine being a carpenter. Your shop has to be massive. Your investment in wood is significant. Your skills take decades to sharpen. And when your work finally reaches a level of perfection, few people can truly afford it. That’s the paradox—mastery often makes the work rarer, but not always more profitable.

Yet I can’t turn away from this path. The detail of the craft pulls me in. Stone carving is an ancient art, one that carries traditions worth preserving. There’s meaning in taking something inert—stone—and giving it a form that might outlast us, transforming it into something that feels immortal.

But the pursuit isn’t easy. Striving for excellence can become a mirror, one that reflects not just our progress but also our insecurities. It’s hard not to feel burdened when the practice demands so much and rewards so little. In times like these, when it feels as if the benchmark for performance keeps climbing higher, it’s tempting to believe that some unseen hand is forcing us to chase endlessly.

This is what I think of as “chasing ghosts.” These ghosts are the illusions of perfection—false visions of what we think we should be, or what others expect us to be. But perfection is an illusion. We are all evolving, becoming truer versions of ourselves, shaped not by flawless outcomes but by persistence, honesty, and individuality.

Sometimes, simply staying true to our craft—whether it’s widely celebrated or quietly overlooked—is more meaningful than any price tag. Art is not only about success in the eyes of others; it’s about grounding ourselves in something real, something lasting.

I hope, in time, we learn to stop chasing these ghosts. To lay them to rest. And to continue forward, more true to ourselves than any imagined version of perfection could ever be.

Tracing the Heavens – An Owl in Stone

A fractured stone, a cherry wood base, and an owl’s elegant pose came together in Tracing the Heavens. Follow the journey of this rare sculpture that named itself.

The thoughts and feelings that come with the artist’s life are important, but every so often I need to pause and reflect on the process itself—how a sculpture is actually made.

Recently, I’ve been immersed in a new piece that revealed its name to me long before I finished carving it. That’s a rare occurrence, and I take it as a sign that the motivation and meaning were already clear before the final details emerged.

The journey began about two months ago when I stumbled across a piece of stone from one of my two trusted stone dealers. It was an odd block—strangely colored with strong fracture lines running in different directions. For most carvers, that’s a definite “no.” Fractures can spell disaster, unless met with careful intention, planning, and a little luck. But I can’t resist a challenge, and I had already bought a similar stone just weeks earlier.

Around the same time, I came across a hollowed knot of cherry wood in a specialty wood shop. For $35, it seemed destined to become the base of one of my signature owls. The block sat waiting in my studio until, one day, I came across a photograph of an owl in an unusual pose—elegant, youthful, stretched upward. It reminded me of my daughter, and I knew instantly: this was the form I needed to carve.

To work out the posture, I sculpted a small plasticine model over 3.5 hours. From there, I scanned it using a lidar app on my phone and imported the model into a 3D program. Having a digital version I could rotate freely gave me a reliable reference alongside my sketches and collage of owl images.

Equipped with a new facemask, a 7” Makita grinder, fresh hand tools, and a custom carving table, I set to work in the studio. The first stage was intense—the grinder raising so much dust I could hardly see until it settled, even with my dust collection system running. Step by step, I shifted to finer burrs and cutters, slowly shaping the fragile stone into something true to the vision.

At this stage, I’m confident in the form, though there’s still a great deal of work ahead. What began as a discarded stone and a forgotten block of wood is taking shape as Tracing the Heavens—a sculpture whose name arrived before the carving was even halfway done.

I’ll share more as the owl emerges from the stone.

Details Matter: From Studio Setup to Digital Presence

Days off often feel like a tug-of-war between carving, enjoying the moment, and keeping up with the details of life. From ticks in the grass to cords in the studio, every detail matters. Recently I streamlined my workspace and updated my portfolio with new works—because the digital presence is just as important as the physical.

The tug-of-war on a day off is real. Part of me knows I need to get downstairs to carve, but the other part just wants to sit outside, sip coffee, and enjoy the breeze. The details matter, though—and I’ve learned the hard way. The last time I ignored the “small stuff,” I missed a tick no bigger than a poppy seed on my foot.

Yesterday’s energy went into prepping my studio: setting up a new carving table, arranging cords and lights, and streamlining everything for safety and efficiency. I like things neat, with each tool exactly where it needs to be. Now the space is ready for the work ahead.

In the spirit of “details,” I’ve also updated my portfolio with a few pieces that hadn’t been shared before—outside of the occasional blog mention. In today’s world, we live in two spaces: the physical galleries where art can be experienced in person, and the digital spaces where it must also live to be found. I don’t have the time or resources to run a shop of my own, so my sculptures find homes in galleries. But managing an online presence has become its own kind of craft, and it takes just as much dedication.

So take a look through my updated portfolio when you can, and explore the new works I’ve added. My efforts in both stone and digital spaces feel more meaningful when they’re seen. And if you’re curious, you can always find more through my YouTube process videos, my Instagram feed, or even on Facebook and Threads. Every detail adds up—and hopefully, each step reveals more of the story behind the work.

Sweater Weather, New Beginnings, and the Upper Canada Native Art Gallery

There’s a quiet joy in sweater weather—the crisp air that clears away summer’s weight and invites gratitude for small moments. Yesterday brought a milestone for me: acceptance into the Upper Canada Native Art Gallery in Niagara-on-the-Lake. The gallery’s historic charm and the kind words of its curator affirmed my path as an artist. Yet even in celebration, the stone still calls—an owl already waiting within soapstone and cherry wood, ready to be revealed with care.

This morning I’m sitting on the porch with a cup of coffee, taking in what feels like the best time of year. Sweater weather—cool air that clears out the heaviness of summer and makes you pause for a breath of gratitude. It’s a reminder that the simplest moments can hold so much weight.

Yesterday was a milestone for me. I was accepted into the Upper Canada Native Art Gallery in Niagara-on-the-Lake—a place my wife and I have always loved for its preserved history and calm spirit. To have my work resting there feels deeply right. The gallery owner, someone with great experience curating sculpture, offered me kind words that helped lift the doubts that so often come with being an artist. As I’ve come to learn, where art finds its home is just as important as the piece itself. My hope is that my work offers the same rest and repose to others that it has given me in creating it.

But even in this moment of gratitude, I feel the pull back to the studio. The next piece is already waiting for me in the stone—a soapstone owl on a cherry wood base. The form is there, hidden inside, and my role is to carve gently so as not to disturb it too soon. With new tools and a fresh workspace ready, I’m eager to begin. Every new work feels like a conversation with the stone, and I’m looking forward to seeing where this one leads.

‘REQUIEM’ - Metamorphosis, Mortality, and the Bear Within

The bear has long been a symbol of wisdom, transformation, and guidance. Through recent life experiences and the creation of pieces like Metamorphose and Requiem, I’ve come to understand my own mortality, my own transformations, and the deep meaning of rest and repose.

There was a word that stuck out when selecting the name of my recent bear. I have to admit (and this fact goes with many of y sculptures), I often find moments of love and distaste. This is obviously a useful quality to have reason to allow some constructive criticism happen (since there isn’t a panel of apes who jury my work over my shoulder). But I digress; the point is the subject matter is one I’ve done many times before but I like to try a pose that is unique to the shape of the stone, but also unique to what I have done before. At this moment, I am satisfied.

You won’t hear a critique often from an artist, but coming from my perspective, it is probably valuable, from another person looking outside, to one’s internal disposition. As in, this reflects our souls need to improve. This experience I can share and perhaps you’ll find some solace in it.

There are certain angles I love this sculpture, but there are certain angles I do not. I think part of that is inevitable due to the nature of bears hidden nature. But also this sculpture in particular. I’ve read from commentators that they like the bears head to be ‘point up’. Yet I do no see this in nature often. They will sniff the air, but only look up if they suspect something. But they are stealth animals for the most part. They weight hundreds of pounds yet can creep through the densest of forests without being heard before even being seen and they are just as good as being unseen as they are unheard. I know. But this all lends itself to being ‘hidden’.

The qualities of the bear are just as mysterious as I’ve always felt. In many Native American traditions, the bear is seen as a carrier of ancient wisdom, a guide, and even an elder kinsman who has taken the form of a bear. Through dreams and visions, they are said to reveal which plants heal, and which paths to follow.

This might sound far-fetched, but I recently went through an experience that confronted me with mortality, and it has transformed the way I see myself and my life. I’ve realized how often I’ve taken my days for granted—living as a provider, a “respectable commoner,” carrying weight on a thin frame until I became something I no longer recognized.

Years ago, I saw this clearly in a photograph with my cousin, someone very much like me. Yet in that photo, I appeared already transformed into the “respectable version” of myself. Looking back now, I see how true it is: we all shapeshift in our own ways.

Now, after this brush with mortality, I feel another transformation unfolding. Some sides of me I do not recognize—and I am making conscious steps to move away from them. We are all in metamorphosis, whether we realize it or not.

I sculpted a piece some time ago called Metamorphose—a polar bear, gazing upward, almost in prayer. To me, it symbolized that genesis of transformation: sitting crushed, yet lifting our spirit high to look to the Creator for help. The slow shift from mind to movement, where grace begins to act on our behalf. It’s no coincidence that this piece found a new home.

Now, I find myself holding Requiem, a sculpture that has accompanied me through the darkest chapter of my life. Its name means “rest” or “repose.” And it became just that for me: a space of deep reflection, a cathedral of silence, where the shifting light of each day reminded me that rest is not idleness, but a sacred part of transformation.

We are transforming, all of us. May you find your own requiem—a place of repose, where light shimmers through ordinary moments like stained glass, illuminating the hidden spirit within you.

Let There Be Light: A Small Change That Transforms Everything

Sometimes the smallest investment brings the greatest realization. Adding a simple light to my workspace revealed more than dust or detail—it reminded me that in both art and life, illumination is what awakens us to what matters.

I had a realization recently that’s changed my approach to both my craft and my life. It came down to one small tweak: more light.

Like any artist, I invest in tools carefully. Each purchase must justify itself in the long run. Two months ago, I decided to add a second LED strip light to my studio—a modest 800 lumens of flexible, battery-powered brightness. I already had one and found it useful, but adding a second transformed everything. With two angles of light, I could see details in my carving that I’d missed before. What was once hidden in shadow became clear.

It struck me: how often do we work in environments with too little light, not just physically but spiritually? No wonder we miss the details.

We’ve all heard the phrase “swept under the rug.” The truth is, much stays hidden in darkness. In our homes, the brightest sunlight of morning or evening reveals dust, clutter, and imperfections we’d rather ignore. Likewise, in our lives, we often dim the light intentionally—closing blinds, staring into screens, avoiding what needs our attention.

But it’s only when the light shines that we can see clearly. Only when we let it in do we realize what needs cleaning, what needs tending, what needs healing. The same is true in our hearts and minds.

All it took was a simple LED light to remind me of this. And it brought me back to an old, timeless verse:

“And God said, ‘Let there be light!’ … and there was light.”

It’s in that light—whether in art, work, or life—that creation begins to appear.

Keeping the Moment Holy: Mindfulness in Stone Carving and Life

Life’s rush often steals our attention, leaving us shallow and restless. Through stone carving and the mindful practice of treating each moment as “holy,” we can reclaim presence, gratitude, and peace in the small rhythms of daily living.

“There’s a rhythm and rush these days, where the lights don’t move and the colours don’t fade.” — José González, Stay Alive

We often find ourselves moving task to task in a blur, rushing through life without pausing to breathe. For me, stone carving is where the rush stops. It’s a mindful practice, a way to return to presence. To carve well, I must set aside the moment—make it “holy.”

In scripture, the Sabbath was meant as a day of rest, set apart from work. It was a practice of abstaining from productivity, a way of fasting from the rush of doing. Ascetic monks extended this rhythm into daily life through abstinence and devotion. In the modern West, we’ve reshaped this idea into what we now call mindfulness—bringing ourselves back into the present moment.

But what if we went a step further? What if every act was set aside as “holy”?

We lose presence in daily life when we lose gratitude. The little things—our morning coffee, sunlight on the window, an old song on the drive home—become invisible. Stone carving has taught me this lesson repeatedly. Some days the work feels like strain and frustration, but when I remember to treat the act itself as sacred, the process shifts. Each mark of the chisel becomes a prayer, a moment of presence, a reminder that the craft cannot be rushed.

Without this, life quickly slips into what González describes as a “world gone shallow and a world gone mean.” The antidote is simple: notice, give thanks, and let each moment last.

We are here only a short while. Let us honor the small rhythms of life as gifts from the Creator—moments set apart, holy, eternal.

The Hidden Spell of Art

Art is more than what meets the eye—it’s an enchantment, a quiet spell cast into the world, often carrying unsaid words and mystery. Unlike mass-produced creations made for easy consumption, true art lingers, challenges, and resonates when the time is right.

Art, at its best, feels like an enchantment—a spell cast by the artist, quietly sent into the world, waiting for the right person to receive it. There are always unsaid words hidden in the work, fragments of mystery that only a few may ever fully understand. And that’s part of the beauty: obscurity leaves room for curiosity, allowing viewers to discover their own meaning in what is unseen.

Not all art is well received, of course. Taste varies endlessly. Some creations are like a bowl of KD—comforting, mass-produced, and easy to digest. But every so often, someone realizes that it doesn’t quite sit with them. They dig deeper. They seek what stirs their soul, what resonates with their unique palette of taste. And when they find it, they know.

As artists, we feel the tension between creating what the masses expect and staying true to what moves us. Repetition and imitation may be safe, but they risk stripping away meaning. A copy of a copy becomes background noise—unquestioned, unexamined. By contrast, something new, honest, and raw always sparks attention, even in the untrained eye.

This is the true challenge and calling of the artist: to resist being lost in the crowd, to tune ourselves to the one note that vibrates in our hearts. Our message will be received—not always today, not always by many, but always by those who are ready for it.

So if you are an artist reading this, take heart. Your work matters. Your voice is heard, whether now or tomorrow. Trust the mystery you weave into your art, because time has a way of revealing it to those who need it most.

Marketing is a Pain in the Arts (and the Arse) for Artists

Marketing is the necessary evil of the art world—but is it stealing the spotlight from real creativity? Here’s why true art often lives in unseen corners, and why you should go looking for it yourself.

Let’s be honest—modern life revolves around sitting on our arses.

We wake up, sit on the toilet, sit down for coffee, sit at a desk job, sit in cars, sit in chairs on vacation, and finish it all off by collapsing on the couch. While we’re sitting, we’re bombarded with marketing telling us what to buy, who to follow, and what’s worth our attention.

Here’s the kicker: I hate marketing. Not because it doesn’t work, but because as an artist, it steals the hours I’d rather spend carving stone. Instead, I’m stuck on my backside again, typing captions and tweaking hashtags. That’s the real pain in the arse.

The truth is, marketing isn’t just about selling—it’s about visibility. And visibility costs. I recently read about a popular artist who spends eight hours a day marketing and maybe squeezes in two hours of actual art. That’s not the balance I want for my life or my work.

So, what happens? You—the audience—end up paying for marketing more than you pay for the art itself. The most visible art isn’t always the best. It’s simply the art with the biggest advertising budget.

But real art—the kind that moves you—is often tucked away in places that don’t scream for attention. It hides in corners, in small studios, in communities where people create because they must, not because they’re playing the algorithm game.

Years ago, I got into geocaching. Sure, the map showed recommended locations, but the real magic came when I wandered off course, exploring unseen paths and stumbling onto places no one thought to highlight. That’s where the beauty was.

Art works the same way. The best pieces might never trend. They won’t buy their way into your feed. But if you look for them—if you go exploring—you’ll find treasures.

So, go out and find art for yourself. Don’t just follow the masses. Otherwise, you’ll end up shoulder to shoulder with the crowds jostling for a glimpse of the Mona Lisa—an artwork so overhyped it’s hard to even see it anymore.

The real stuff? It’s waiting in the quiet, unseen places. And I promise, it’s worth the hunt.

Borrowed From the Forest: Backyard Lessons in Balance and Belonging

My backyard is more than just a patch of green—it’s a living sanctuary where trees, animals, and balance thrive. It reminds me daily that we borrow from the forest and owe our respect in return.

On days like this, life feels simple and good. I’m sitting at the back of the house in the shade, looking out at the yard soaking in the sun. It’s not the manicured grass of suburbia, but a patchwork of ground cover—clover, moss, and other wild plants that keep it lush and green even in the hottest seasons.

Around the edges, country-tough perennials thrive without needing any care, surviving droughts with ease. A willow-like tree stretches its long branches low to shelter the cool, shaded corner where I sometimes carve. In the back corner, a towering spruce provides the squirrels with pinecones and endless climbing ground. Two stubborn vines compete for the sun across the pagoda, while elderberry trees quietly prepare for their fruit.

It’s a small space, but a complete little ecosystem. A balance. A haven. Animals know it too—they return year after year, trusting me enough to linger instead of scattering at the first sign of movement. I’ve invested plenty into food to keep them coming, partly for my daughter’s joy, but also because their presence makes this place feel alive.

Why keep it this way? Because this backyard isn’t truly ours—it’s borrowed from the forest. We’ve carved our homes and yards out of wild ground, but the truth is, we belong to it as much as it belongs to us.

Spending time among animals has always reminded me of this. Their character qualities resonate with us—we borrow their sounds, their quirks, even their wisdom. Many animistic traditions see animals as messengers of deeper mysteries, truths still invisible to the Western mind. They honor the creatures in a way we often forget to.

Our modern way is different—we cultivate, harvest, and consume. And yet, even in small choices, we can reconnect. I recently tasted grass-fed milk again, and the difference from conventional milk was striking. My family has roots in cattle farming, so I know the richness of well-fostered animals. It was a reminder that care and respect change everything.

I don’t pretend to know it all. In fact, the more time I spend among animals and plants, the more I realize how little we truly know. But what I do know is this: we are kin. We borrow from each other’s lives. And if we must borrow, we should also give back.

So I carve, I observe, I give space. And I remain grateful—for this backyard sanctuary, for the animals who return, and for the reminder that all of this is borrowed from the forest.

Here’s to another day in the studio.