When the Mind Steps Aside: Discovering the Hidden Hand in Art

I believe I’ve stumbled upon something remarkable—perhaps even groundbreaking—about how we live and create with intention. It’s an insight into what happens when we trick the left brain—that logical, critical part of ourselves—into stepping aside long enough for something greater to emerge.

My high school art teacher used to say, “Let the right brain take over.” He’d crank up the music, stop teaching technical details, and just let us create. The idea was simple: music and rhythm help us shift from the analytical left hemisphere to the intuitive right. In that space, we loosen up. We begin to feel more than think.

Neurologically speaking, when the left brain quiets down, we can enter a blissful, flow-like state. But if it shuts off completely, we lose access to logic, speech, or even basic coordination. So the magic seems to live in that in-between—where intellect hums quietly in the background while intuition takes the lead.

The Experiment with My Daughter

A few days ago, I was looking at Pinterest images of polar bears before sitting down to draw with my daughter. She loves to scribble freely, without rules or expectations. Sometimes she’ll glance at her drawing and casually say, “cat,” or “bird,” and sometimes I may grasp something alike out of it.

Inspired, I decided to draw the way she does—fast, loose, without trying. About 25 seconds in, while my hand moved almost unconsciously, a polar bear’s face began to appear from the chaos of scribbles. Upside down, no less. And astonishingly, it was better—more alive—than what I could have drawn had I tried.

A few days later, I tested it again—drawing upside down this time while she watched from across the table. Again, the result was more natural, more expressive, more true.

The Great Egret Revelation

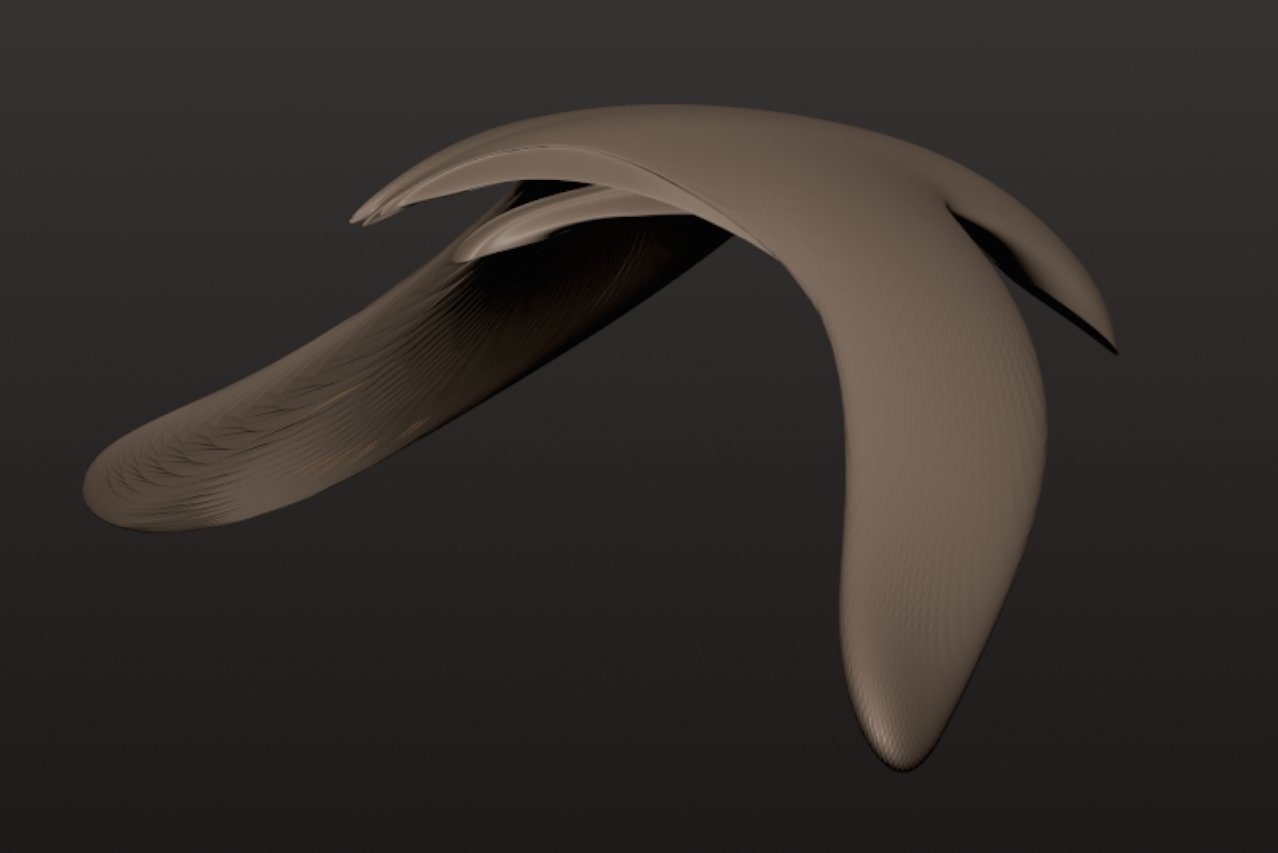

Recently, I was refining a 3D model of a Great Egret—a tall, elegant heron-like bird. I spent hours fine-tuning the proportions and details, guided by countless reference photos. Then, I put the file aside and started working on something abstract, purely for play.

And then it happened again. Out of the freeform shapes, without planning or intent, emerged the unmistakable form of a Great Egret. The likeness was uncanny—and somehow more beautiful than my deliberate, technical render.

That’s when I realized: my intellectual mind had laid the groundwork. It had studied, measured, analyzed. But it was only when I let go—when I stopped trying—that something extraordinary appeared.

The Art of Doing Without Doing

In Zen, this is known as Wu Wei (or Wei Wu Wei): doing without doing. It’s the state of effortless action, where mastery and surrender become one. The Zen archer doesn’t aim with his mind—he allows the arrow to find its target through presence.

There’s a story of a master archer who, when challenged by a student, drew his bow in complete darkness and split the back of a previous arrow. The shot was not a display of skill, but of connection—between spirit, mind, and motion.

Becoming the Instrument

In the same way, when artists let go of the ego—the “little self” that needs to control and perfect—we make space for something larger to flow through us.

Remote viewers describe a similar process: using intuition to perceive distant targets with uncanny accuracy, bypassing logic entirely. Could it be that this same something—this consciousness beyond the intellect—moves through us when we create?

Maybe true art begins where the self ends.

When we lend ourselves to something greater than our technical mind, we receive what can only be described as extraordinary. The key is learning how to let the extraordinary happen—by getting out of our own way.

Looking Up: Lessons from an Owl and the Art of Letting Go

A reflection on carving, faith, and fatherhood—how one artist found spiritual meaning in a barn owl sculpture that reminded him of his daughter and the importance of looking up.

There are times I’ve fallen in love with a sculpture as I’ve been working on it. Perhaps I’m not the only one who’s felt this way—but for me, it’s increasingly rare. The constant inner critic is always present, whispering in the background, even as the artist within searches for appreciation and gratitude in the process. At some point, those two voices—the critic and the creator—merge. And in that merging, something magical happens: flow. The careful turns careless, the mind quiets, and the stone begins to speak.

The last piece I produced began with an extraordinary reference—a young barn owl, wings slightly spread, head raised toward the sky as if watching the heavens. The posture reminded me of my daughter. That innocent, upward gaze of wonder. How often do we forget to look up as we grow older? As we stand taller, we begin to see others as peers—or worse, as competition—each of us fighting never to look up again.

But maybe looking up is exactly what we need to do more often.

Our mission, whether as artists or simply as people, is to remain teachable—to learn from something higher, to serve others as if we were entertaining the children of God. To be both young and old at once requires humility and adaptability. It calls on us to forgive, to turn the cheek, and to love even our adversaries.

When I carve an owl, I often sense that same paradox: a creature both feared and revered. Its silent watchfulness commands respect, but in its eyes I see gentleness, understanding, and beauty. In this particular owl, I saw my daughter’s spirit—bright, alert, full of promise.

So when it came time to bring the sculpture to the gallery in Niagara-on-the-Lake, it wasn’t easy. Letting go never is. Yet, I know there will be more. I will see my daughter in many future works and strive to make each piece more beautiful than the last—for love’s sake, for the art, and for whoever the piece connects with. Because in the end, we’re all connected in ways we can’t yet imagine.