Anima, the Barn Owl, and the Threshold Beneath the Wing

From Mesopotamian reliefs to esoteric symbolism, the barn owl has long been tied to hidden knowledge, liminal spaces, and the silent weight of ancient memory.

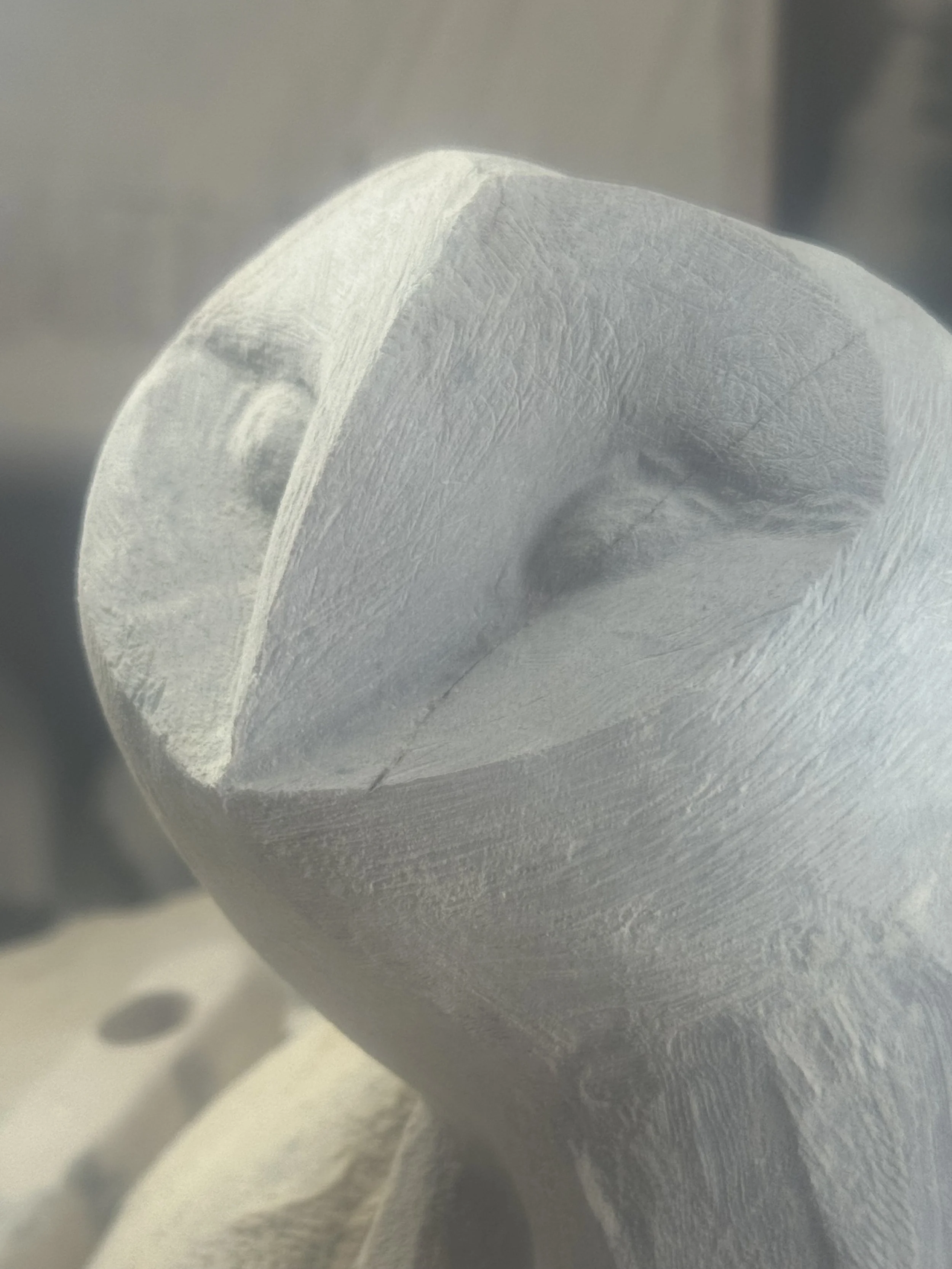

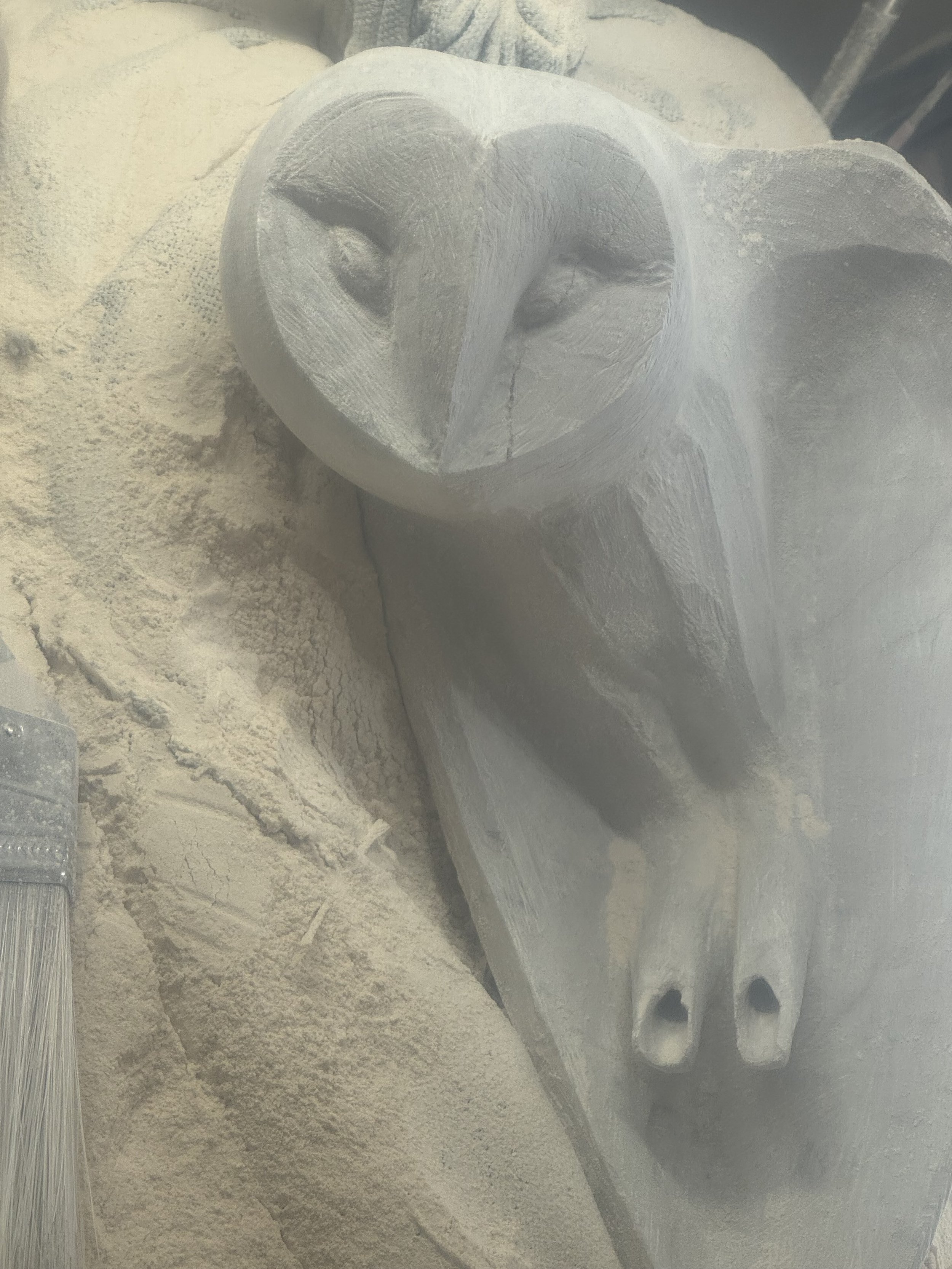

I’ve had a bit of time recently to return to another barn owl project, and as often happens when I work with this form, it’s pulled me back into deeper reflection. Not just about anatomy or gesture—but about why this animal continues to surface in human imagination, across cultures and eras.

The barn owl feels less like a subject and more like a metaphor that predates us.

Across history, the owl has occupied a complicated and often contradictory role. In parts of Africa, owls have long been associated with witchcraft and shapeshifting, seen as emissaries between worlds or forms assumed by practitioners who move unseen. In other traditions, particularly within early Western esoteric and fraternal symbolism, the owl becomes a figure of hidden knowledge, night wisdom, and watchfulness—sometimes even linked, symbolically, to darker or more ambivalent forces.

There are interpretations that connect the owl to Molech imagery within early fraternity symbolism—often pointed out in discussions of the American dollar bill, where the owl is said to hide in the folds and corners. Whether literal or symbolic, these readings speak less to historical certainty and more to the owl’s enduring association with secret knowledge, thresholds, and power held in silence.

What’s striking is how far back this goes.

The earliest known appearances of owl imagery appear in Mesopotamia, and possibly even earlier. The most well-known example is the so-called Burney Relief (often linked to Lilith), where owls flank a winged female figure—an image saturated with themes of night, sexuality, sovereignty, and the liminal. In these early contexts, the owl is not softened or romanticized. It is potent, unsettling, and deeply tied to the unseen forces of the psyche and the world.

This is where Anima continues to live for me.

In Jungian psychology, the anima represents the inner soul-image—the intuitive, unconscious, feeling aspect of the psyche. It is not polite. It does not speak loudly. It appears in symbols, dreams, animals. The barn owl, nocturnal and soundless in flight, feels like a perfect carrier of this energy: perceptive without display, powerful without aggression.

As I worked on this piece, my attention kept returning to a small but essential structure: the tarsus.

In the anatomy of the barn owl, the tarsus is the quiet pillar of balance—the slender segment that carries weight, absorbs stillness, and allows the body to remain suspended between earth and air. It is a place of grounding rather than motion, often unseen, yet essential.

Though it shares no linguistic origin, the word tarsus echoes the ancient city of Tarsus, a historical crossroads where philosophies, religions, and inner traditions converged. The parallel is symbolic rather than etymological—but meaningful nonetheless.

Here, the tarsus becomes a metaphor:

a threshold between movement and rest,

between the visible and the unseen,

between instinct and awareness.

Like the owl itself, this form occupies the liminal—rooted firmly in the physical world while oriented toward the silent, the nocturnal, and the intuitive. The strength lies not in force, but in steadiness; not in flight, but in what makes flight possible.

In returning to the barn owl, I don’t feel like I’m repeating myself. I feel like I’m circling something ancient—something that keeps revealing itself slowly, layer by layer. Perhaps that is the nature of Anima itself: not something to be solved, but something to be approached with patience, weight, and listening.